How Hungarians Used "Wagenburg" Tactics in 15th Century

The use of war wagons in the crusades against the Ottomans.

The medieval war wagons are associated with the Hussites and the Hussite Wars of 1419-1434, where they were used against armored mounted knights with great success. But they spread to other parts of Central Europe soon after that, and remained popular for the rest of the century.

The Hungarian hero John Hunyadi famously used the “wagenburg” (wagon fort) tactics against the Ottomans in his various crusading campaigns in the Balkans.

600 war wagons were used for the Crusade of Varna in 1443-44. These were produced in Brașov in Transylvania under the supervision of a certain Czech master who was experienced in wagenburg warfare. Another Czech, a captain named Jan Čapek, was entrusted the leadership of the wagenburg formation. He was a veteran warrior who had fought under the famous Jan Žižka, who was a pioneer of such tactics in the Hussite Wars. In this manner, the knowledge of the Hussites was transmitted to other parts of Central Europe and the wagenburg would remain a popular tactic for the rest of the century.

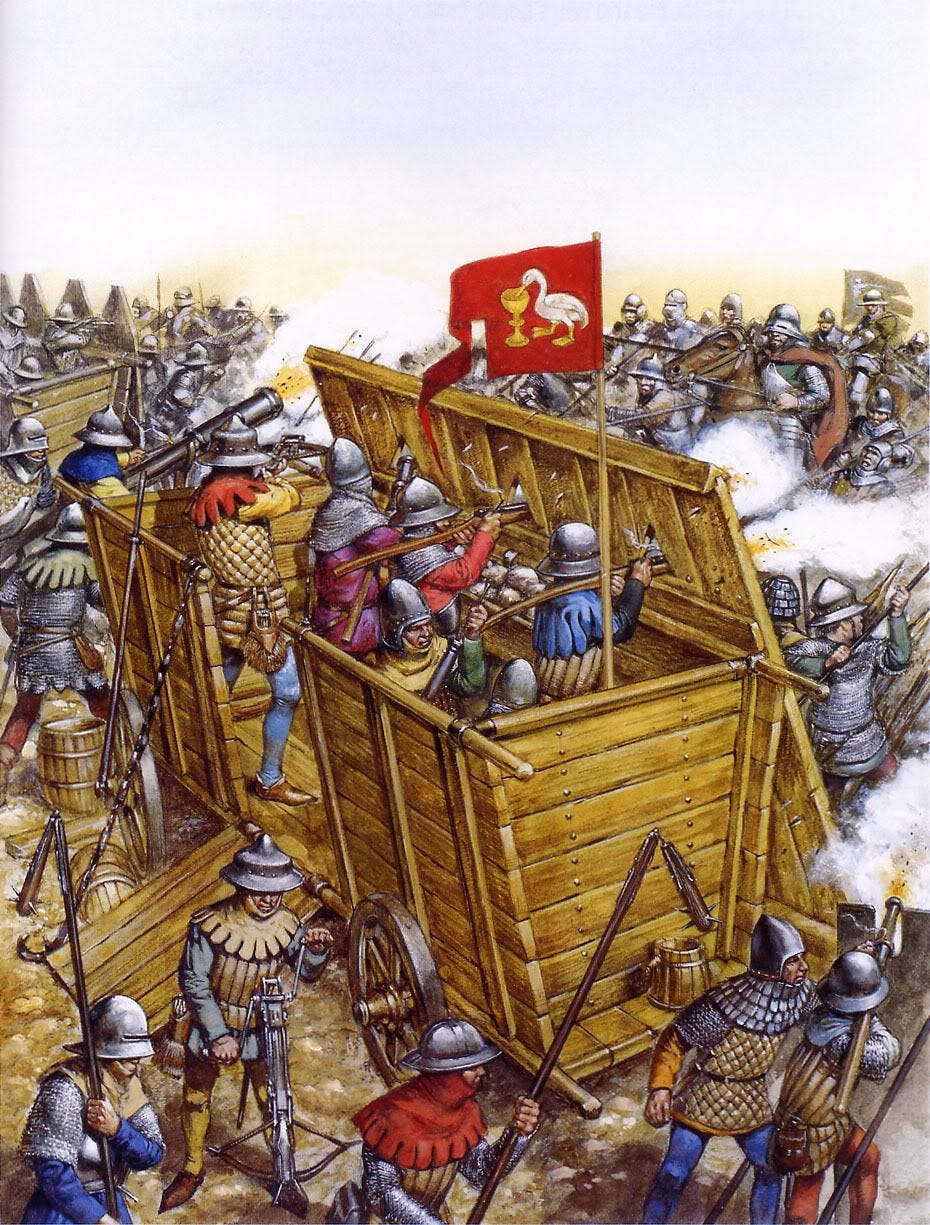

Hungarian war wagon, middle of 15th century.

First I would like to briefly talk about how these tactics emerged. They were first used in the said Hussite Wars which lasted from 1419 to 1434. The Bohemian Hussites used them to fight against armored knights and achieved much success. They formed a square of war wagons, joined them with iron chains and defended this “wagon fort” (vozová hradba in Czech or Wagenburg in Germans) with missiles from crossbows, handguns and artillery. The crew of each wagon consisted of around 20 soldiers and included men armed with melee weapons, who would fight if the enemy came close or broke into the wagenburg.

Due to the success of the Hussites in war and the spread of their movement, their tactics caused a lot of curiosity and the veterans from the Hussite Wars began serving as mercenaries in neighboring European countries. This is how the wagenburg spread to Hungary.

A letter from 1441 gives an example of how the wagons forming a wagenburg would be equipped in Hungary. In this letter Queen Elizabeth asked the burghers of Pressburg to equip five war wagons. She details that each one of these wagons should include four handguns, a large gun, a houfnice (cannon), and a tarasnice (a smaller type of cannon). We can assume that the war wagons used on the Crusade of Varna were similarly equipped. Due to lack of local quality infantry in Hungary, a lot of mercenaries had to man the wagons, mainly Czechs and Germans.

The wagenburg tactic was primarily a defensive one, trying to lure a larger army into a deadly fire from the wagons, which were placed close to each other, forming an improvised fort, from which infantry and artillery could fire on the approaching enemy and defend itself from assaults.

It was especially useful against mounted armored knights, who were forced to dismount and were exposed to gunpowder weapons which could penetrate their armor.

Hussite war wagons in action. The knights are unable to penetrate the wagenburg.

But this tactic also had deficiencies which showed in battles against the Ottomans during Hunyadi’s campaigns, of which I will talk about now.

The main problem was that, due to its defensive nature, the wagenburg only really worked if the enemy assaulted it, or ended up in the range of its artillery. It worked against aggressive European knights, but the Ottomans brought other things to the table. They had an organized infantry, a mobile cavalry that could outflank the opponent, and sheer numbers with which they could overwhelm the usually smaller Christian armies. They posed a lot of different threats on the battlefield. Furthermore, Hunyadi was the one bringing the war to them, so he was forced to take offensive approach.

John Hunyadi was a Hungarian nobleman who had already made a name for himself fighting against the Ottomans and defending the Transylvanian borderlands. When the Pope called for a crusade in 1443, which would become known as the Crusade of Varna, Hunyadi was seen as the perfect commander to help drive the Ottomans from the Balkans. The crusade was well funded and involved King of Poland and Hungary Władysław III, who was also one of the leaders of the crusade and would eventually die in battle, as well as other important nobles. The crusade had an ambitious goal to expel the Ottomans, who had certain internal troubles at the time, from Europe.

Hunyadi initially defeated the Ottomans at the Battle of Nish in November of 1443 but could not pass through the well defended Zlatitsa Pass and was later defeated at Melstica. There he tried to lure the Ottomans into attacking his wagenburg, but the Ottomans were wary of it and simply refused to engage it. They were already familiar enough with this tactic that they knew it was a death trap, and could not be tricked in this way.

The crusaders were forced to retreat and won another battle against a pursuing Ottoman army at Kunovica in 1444. Despite the failures, this so-called “long march” was considered a success as Hunyadi was able to penetrate deep into Ottoman territory, and another campaign would soon follow, which would culminate at the Battle of Varna that same year. The crusade continued.

However the campaign of 1444 was too ambitiously planned and the crusaders ended up being cornered near the fortress of Varna by a much larger Ottoman army, caught between the Black Sea and Lake Varna. The Battle of Varna followed.

Cardinal Julian Cesarini, who was present in the crusader army, suggested that they should form a large wagenburg. But as shown by the previous experiences, the Ottomans were unwilling to engage a wagenburg. This would mean that the crusaders would eventually run out of supplies, had they taken this approach. They decided for an aggressive approach instead, putting everything on the line by attacking the Ottomans.

The wagenburg tactic could therefore not be used effectively at the Battle of Varna, where the crusader army was forced to fight offensively. The crusaders placed the wagons in a line behind the army instead. This served to protect the rear, and it also discouraged the soldiers to flee the battlefield to seek protection in a closed wagenburg. This was evidently an emergency measure that guaranteed that the soldiers would fight offensively and would not retreat.

The aggressive approach against a larger army ultimately failed and the crusaders suffered defeat. However, as the battle progressed, some of the crusaders eventually took shelter behind the wagons and quickly set up an improvised wagenburg. The Ottomans were forced to stay out of the range of artillery and waited for the crusaders, who were in a desperate position, to surrender.

Hunyadi had already successfully fled and survived to fight another day. At the Battle of Kosovo in 1448, where he would fight against the Ottomans again, he employed the wagenburg in the traditional way where the wagons were tied to each other with chains and cannons installed in the gaps in between. But the Christian forces suffered another defeat in a battle that lasted for days.

During this battle, the wagenburg served as a last refuge, and did not play crucial part in the tactics. The battle was lost when the crusader cavalry was defeated, and when the heavily armored infantry was crushed as well. Lacking the cavalry support, the remaining infantry that took refuge inside the wagenburg was in a hopeless position. The crusaders in the wagenburg were eventually overwhelmed by Ottoman infantry which broke into the wagenburg and “partly cut down those they found inside, partly took them prisoner.” It is said that the Germans and the Czechs fighting in the wagenburg perished to the last man.

However the wagenburg tactics did work in some other situations during Hunyadi’s campaigns. There is an account that in one particular skirmish, Hunyadi placed wagons manned by archers and equipped with small-calibre cannon to the Ottomans’ rear while he launched an attack on their front, driving them into the deadly wagenburg.

Wagenburg. A contemporary depiction.

Hunyadi, who survived the defeat at Kosovo in 1448 as well, would eventually win a big battle against the Ottomans at Belgrade 1456, but this victory was not won with wagenburg so I won't talk about it here.

Hunyadi’s son Matthias Corvinus, who became King of Hungary in 1464, also used war wagons. His campaign to conquer the fortress of Šabac in 1476 included 3,000 carts used for making a wagenburg. But Corvinus’ mercenary Black Army was a very versatile force which relied on cavalry much more than on infantry. Furthermore, Corvinus preferred to protect his infantry with large pavise shields rather than with war wagons. Cavalry also had a much more prestigious position than infantry in his army. Most of his infantry captains were townspeople of non-noble backgrounds, people for whom a career as a cavalry captain would have been out of reach. This shows how Corvinus assigned much more worth to cavalry.

Corvinus knew that to defeat the Ottomans, he needed mobility. He used both heavy and light cavalry to great effect and his army defeated the Ottomans at the Battle of Breadfield in 1479, which was a cavalry battle.

But wagenburg tactic was still used into late 15th century and beyond and could be very lethal when the enemy forces tried to engage it and did not have sufficient numbers to break through. An example of this happened in 1502 near the Bosnian town of Jajce. Hungarian nobleman János Tárcai led a small army to provision Jajce. His train contained 1,000 cartloads of wine, “because without that nothing is done here”, and another 1,000 wagons loaded with all the other necessary materials.

As they were approaching Jajce, the Hungarians pitched their camp on a hill nearby, as night was already falling. Tárcai arrayed his wagons in a protective formation, effectively forming a wagenburg. In the morning, a large Ottoman army numbering more than 10,000 men decided to attack the wagenburg. Fierce fighting ensued and the Ottomans were eventually repelled. The Ottomans then decided to feign a retreat, hoping to lure the defenders out of the wagenburg. The Hungarians did leave their camp to follow them, but only followed them for a short distance. There, they turned and lured the enemy cavalry to within firing distance of the artillery installed on the wagons, which had been made ready for shooting in the meantime. The trap worked and Ottomans suffered heavy casualties. The next day, the Hungarians were able to defeat the remaining Ottomans with a joint cavalry and infantry attack, killing more than 1,000 in this assault. Many fleeing Ottomans were also cut down by locals in the Bosnian mountains.

This shows that the wagenburg tactic was still very effective in certain situations even into 16th century. It was especially useful fighting against irregular Ottoman cavalry in Bosnia and Croatia. In 1525, Croatian nobleman Christoph Frankopan repeated the deed of János Tárcai, delivering food to besieged Jajce, using a similar wagenburg tactic by placing his gunners behind carts and fighting a series of skirmishes with the pursuing Ottomans. This earned him the nickname “the hero of Jajce”.

But at the time wagenburg tactics were already becoming obsolete in open battlefields in Europe due to development of pike and shot tactics. The wagenburg was especially vulnerable to artillery and could be overcome by organized and determined infantry. This happened at the Battle of Wenzenbach in 1504 during the War of the Succession of Landshut where Maximilian of Habsburg’s troops, consisting of Landsknecht pikemen, defeated the Bohemian mercenaries employed by the Palatine faction. The Landsknechts broke through the Bohemian wagenburg and achieved a victory.

In the pike and shot tactics, the gunners were protected by pikemen instead of wagons. However the development of pike and shot tactics never really reached Kingdom of Hungary which would soon face a disastrous defeat at Mohács in 1526. Hungary did not have the social conditions necessary for development of urban militias such as the Flemish and the Swiss, and there was no specific pikemen mercenary culture such as the Landsknechts. This meant that there was no significant local pikemen infantry to recruit from, and hence the pike element was missing. For this reason, Hungarians kept using the wagenburg tactics longer than other Westerners. At the Battle of Mohács, wagenburg was formed but it helped little as the numerically inferior Hungarian army could not stop the Ottoman onslaught.

The Battle of Mohács. Notice the Hungarian wagenburg in the top left corner!

My main source for late medieval Hungarian use of wagenburg tactics was the wonderful book by Tamás Pálosfalvi, From Nicopolis to Mohács: A History of Ottoman-Hungarian Warfare, 1389–1526, which I would definitely recommend to anyone interested in late medieval warfare.

Thank you for this article. We may also recall that more recently the Boers used something similar to defeat the Zulus at Blood River, and that in less politically correct times Hollywood used to show settlers from a circle of wagons shooting down redskins until the US cavalry arrived to chase off any survivors.

Amazing article man, I absolutely devoured this one