How King Manuel I of Portugal sent an elephant as a gift to Pope Leo X in 1514

The touching story of the popular elephant Hanno, "a beast not seen in Rome for a long time."

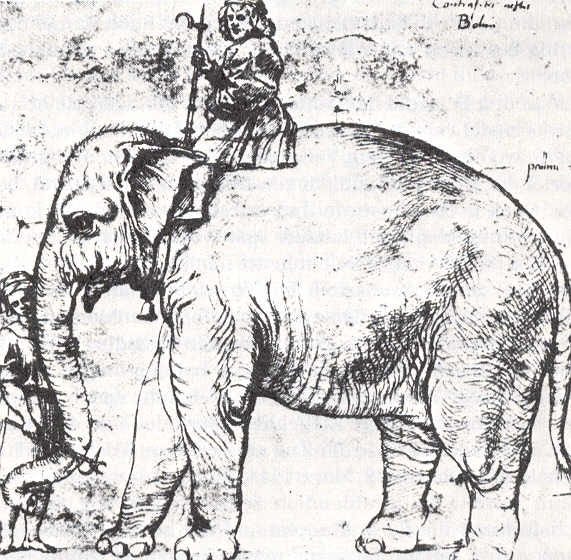

In 1514 an elephant arrived to Italy from India by way of Portugal. It was a gift from King of Portugal Manuel I sent to Pope Leo X who had just been elected a year earlier. The pope named the elephant Hanno, or Annone in Italian, a reference to the famous Hannibal who crossed the Alps with war elephants so many centuries earlier.

King Manuel I sent other exotic animals and splendorous gifts to the Pope, but it would be the elephant Hanno that would receive by far the most attention and become the Pope’s favorite. Leo X described how Hanno provided him “with the greatest amusement and has become for our people an object of extraordinary wonder.”

“It was the elephant which excited the greatest astonishment to the whole world, as much from the memories it evoked of the ancient past, for the arrival of similar beast was fairly frequent in the days of ancient Rome.”

Pope Leo X thanking King Manuel I for the gift of elephant Hanno in a letter.

The story of Hanno the elephant is also the story of these two powerful men of their time, King Manuel I and Pope Leo X.

Manuel I became the King of Portugal in 1495 in rather lucky circumstances as he was not the next in line but following the death of Prince Alfonso in 1491, Manuel’s cousin King John II eventually named Manuel as the heir after he failed to secure the throne for his illegitimate son Jorge de Lencastre. This turn of events earned Manuel the nickname “the Fortunate”.

He was fortunate during his reign as well. His rule saw Portugal transforming from a small country in the corner of Europe to a powerful maritime empire which established a significant presence in lands far away from Europe. Portuguese exploration and naval power built the foundations for this small kingdom to rise to the kind of global empire unprecedented for any medieval kingdom, and pretty much unprecedented in world history as well.

But Portugal also took a lot of inspiration and legitimacy from its medieval past during the reconquista and the crusades against Moors which build the identity of this country. Portuguese naval ambitions were phrased in similar language of the crusades, justifying their imperialism as a sort of revived global crusade against Muslims and pagans in lands far away.

In June of 1505, King Manuel I boasted to Pope Julius II, Leo X’s predecessor, about the lands he intended to conquer for Christendom.

“Receive your Portugal, not only Portugal but also a great part of Africa. Receive Ethiopia and the immense vastness of India. Receive the Indian Ocean itself. Receive the obedience of the Orient, unknown to your predecessors, but reserved for you, and that being already great will be, through God’s mercy, each time greater.”

Manuel’s ambassador to Pope Julius II in 1505.

Remarkably, Manuel delivered on these grandiose promises to a large extent. In the following years, Portugal would indeed have a strong presence in the lands he listed. While they lacked enough men to fully conquer these vast territories, the Portuguese did hold many important ports and trade routes, focusing on controlling the seas.

Most crucially, Portugal expanded influence in Indian Ocean, winning the battle of Diu in 1509 against a coalition of local powers Mamluk Sultanate, Gujarat Sultanate and the Kingdom of Calicut. Afonso de Albuquerque, the ruthless and capable Governor of Portuguese India, conquered Goa from the Bijapur Sultanate in 1510 and Malacca from the Malacca Sultanate in 1511. These battles were won thanks to Portuguese technology and determination. They combined the Western military tactics with their own naval knowledge and improvisation, catching the local powers off guard. Albuquerque also applied terror and cruelty to keep the population in submission and his enemies terrified.

King Manuel seems to have been a genuinely religious man who invested a lot into missionary activity in these newly conquered lands and beyond. He also promoted the idea of reviving the crusades to the Holy Land. He carried the mentality of a ruler from the old medieval world while using modern technology to conquer the new world.

But at the time, Papacy was not able to rally Europe behind crusades. During the pontificate of Julius II it was involved in the long Italian Wars which would soon start to involve almost entire Europe. The machiavellian pope Julius II himself instigated the War of the League of Cambrai which started in 1508, ironically as a sort of “crusade” against the excommunicated Venice by the Papal States joined by the Europeans powers France and the Holy Roman Empire. However the alliances would shift and the war dragged on for years, with the Pope ending up on the side of Venice at some point, and then on the opposite side again. Pope Julius II would not live to see the end of this war as he died in 1513. The Italian Wars were a decades long conflict that sucked all the European powers in and made them unable to come together for a crusade. In fact, some would rather ally to Muslims for their own interests. Portuguese expansionism was also seen as a threat to many established Christian merchants as well as it disrupted the old trade connections. Not everyone in Europe was glad about Portuguese adventures.

The new pope Leo X would inherit this volatile situation. Born as Giovanni di Lorenzo de' Medici, he was elected Pope on 9 March 1513. Coming from the powerful Medici family, he was elected purely for political reasons rather than for his piety. He was not even a priest when he was elected, and would go down in history as the last non-priest to become Pope. He was only ordained priest six days after he became Pope on 15 March 1513, and consecrated as bishop two days later.

Unlike King Manuel I who was in many ways still a medieval king in his worldview and mentality, Leo X was a renaissance man through and through. A hedonist who adored fine culture and arts, he was reported to have said after becoming pope, “Let us enjoy the papacy since God has given it to us.” While some dispute whether he actually said this quote, it no doubt captures the spirit of his papacy. He would spend lavishly and run the papacy into debt.

A man of humanist education, Leo X adored classical antiquity and became a patron of renaissance artists such as Michelangelo and Raphael with whom he had a close relationship. Poets were also numerous in Rome. He turned Rome into a center of European culture. He revived the Roman university and promoted science. During his reign, Catholicism seemingly assumed a pagan Greco-Roman character while Rome turned into a capital of cultured hedonism. But this also carried consequences. Ultimately, Leo X’s reign saw the beginning of Lutheranism to which he could not answer adequately. It was his lavish spending that led to out of control sell of indulgences which were so heavily criticized by Luther in his Theses in 1517. Leo X’s papacy would mark the beginning of the end of unified Latin Christendom as it existed in the middle ages.

But in 1514 when Leo X received Hanno the elephant as a gift from King Manuel I, these problems were still far away. Manuel I knew that he needed to impress the freshly elected Pope by sending lavish exotic gifts. This was not just a way to buy favors with the Pope but also to show off the might and splendor of his kingdom. He also needed the Pope as his ally to legitimize his expansionism. Sending exotic animals was a great way to boast about the reach his kingdom now had following impressive conquests. Along with the elephant Hanno, Manuel also sent other exotic animals to the Pope such as leopards, rare birds, strange dogs and a Persian horse. These gifts were supposed to make a lasting impression on the Pope and the people who would witness them.

It was Hanno who made the biggest impression. The white elephant was sent from India by Albuquerque and it was a miracle that the large animal survived the long journey from the west coast of India to the royal court in Lisbon. The elephant arrived to Italy from Portugal in 1514, around 4 years old at the time. Immediately after arriving to Italy, the journey of Hanno and other exotic animals from the port to Rome already attracted huge attention as workers from the towns, peasants from the fields and gentlemen from their villas were all curious, “avidly seeking a view of the great animals.”

It is said that once he reached the Pope, the elephant Hanno dropped to his knees before Pope and later sucked water into his trunk and sprayed it on everyone assembled, including the Pope. Hanno became immensely popular in Rome where he was first kept in an enclosure in the Belvedere courtyard and later moved to a specially constructed building. Hanno was paraded through streets on many occasions and masses came to see the curious large beast. But these processions would often end in chaos. The elephant would panic from noises on parades such as trumpets or cannons and some spectators would get injured. Nevertheless this didn’t seem to deter people from putting on these spectacles.

These processions in many ways embodied the papacy of Leo X. They were over the top, spectacular, lavish, but also reveal a fascination with going back to what they perceived as classical Rome. Leo X commented on his love for Hanno, “One is almost tempted to put faith in the assertion of the idolators who pretend that a certain affinity exists between these animals and mankind.”

Unfortunately, Hanno would not live long. In 1516, two years after arriving to Rome, Hanno fell sick. The doctors had no clue how to take care of such animal and the popular elephant would soon die of illness, with the Pope at his side.

Such was the end of this animal.

However Leo X made sure his favorite pet was properly commemorated. He commissioned his favorite artist Raphael to design a memorial fresco while he himself composed this touching epitaph:

Under this great hill I lie buried

Mighty elephant which the King Manuel

Having conquered the Orient

Sent as captive to Pope Leo X.

At which the Roman people marvelled,

A beast not seen for a long time,

And in my brutish breast they perceived human feelings.

Fate envied me my residence in the blessed Latium

And had not the patience to let me serve my master a full three years.

But I wish, oh gods, that the time which Nature would have assigned to me,

and Destiny stole away,

You will add to the life of the great Leo.

He lived seven years

He died of angina

He measured twelve palms in height.

Giovanni Battista Branconio dell'Aquila

Privy chamberlain to the pope

And provost of the custody of the elephant,

Has erected this in 1516, the 8th of June,

In the fourth year of the pontificate of Leo X.

That which Nature has stolen away

Raphael of Urbino with his art has restored.