How the Portuguese Fought Against African Kingdoms in Angola in 16-17th Centuries

In their effort to expand the colony of Angola, the Portuguese fought against neighboring African kingdoms. How these wars were fought and what military tactics were used.

In 16-17th centuries the Portuguese fought many wars against powerful African kingdoms as they tried to expand their colony in Angola.

In this article I will explain how these wars were fought and what kind of military tactics were used. In the second part of the article I will also describe how the Portuguese established their colony in Angola and how they got into conflict with neighboring African kingdoms, giving a brief overview of political history of the region during this time.

This is a very interesting and overlooked part of history. It seems that for most people, European colonialism in sub-Saharan Africa is primarily associated with 19th and 20th centuries. This appears to be especially true for military history, as the dominant image people have of European empires fighting against local African armies is that of Europeans, powered by the Industrial Revolution and possessing vastly superior technology and advanced military tactics, beating much larger local armies which were ill-prepared for such warfare.

But there was a lot going on before the 19th century in some parts of sub-Saharan Africa. Wars were fought between Portuguese colonial outposts and their African neighbors as early as 16th century and continued from there all the way to modern era.

During the time I will write about here, the 16-17th centuries, the wars between European empires and local African kingdoms were fought on much more equal terms than in 19th century. The Portuguese in Angola were few in numbers and their European military technology and tactics were not good enough yet to give them a decisive advantage over the large African kingdoms they bordered with, namely the Kingdom of Kongo and the Kingdom of Ndongo, with both of whom the Portuguese fought a number of wars.

Such troops were used by the Portuguese in Africa. Source: David Nicolle, The Portuguese in the Age of Discoveries c. 1340-1665 (Osprey Publishing, 2012), page 32.

At the time, the European empires only had limited logistics to reinforce their colonial outposts, and Portugal was small to begin with and had limited manpower. As a result, the Portuguese in Angola had to use a large number of African mercenaries and auxiliaries and adapt to local African warfare, combining European and African military tactics. Even Portuguese Angolan garrisons had a lot of people of African and mixed ancestry. The Portuguese authorities agreed that no distinction be made between “whites, mulattos and free blacks” serving in Angolan garrisons and promotion was on merit alone. A mulatto named Luís Lopés de Sequeira would become one of the most successful Portuguese commanders, winning the Battle of Mbwila against the Kingdom of Kongo in 1665. To a large extent, the Portuguese army in Angola was basically an African army with European officers and some European troops.

The Portuguese who gained experience fighting in Angola learned to respect local African tactics and did not try to train their African auxiliaries in European tactics. For example when Luis Mendes de Vasconcellos, a veteran warrior with vast experience from Europe who fought against the Ottomans and in the Army of Flanders, became the Governor of Portuguese Angola in 1617, he commanded the army to close up as they were formed loosely in open order as they were used to in local warfare. He tried to make the Africans fight in closed order formations like the Europeans. But he was immediately advised by experienced colonial troops from Portuguese Angola that the open order was better suited for warfare in these lands. António de Oliveira de Cadornega, who came to Angola in 1639 and participated in many wars there, wrote a chronicle in 1680-81 as an experienced veteran of Angolan wars. In his work he often complained about the incompetence of newly arrived European officers who did not understand the local art of war and foolishly lost battles and troops as a result.

One of the main reasons why warfare was very different in Angola from what the Europeans were prepared for was the lack of cavalry. Horse breeding and maintenance was very difficult in many parts of West and Central Africa due to tsetse flies which caused sleeping sickness disease in cattle and horses, which led to high horse mortality. As a result, cavalry was very limited in western African military systems and completely absent in central Africa. The Portuguese tried to introduce it and imported some horses, as they realized very early that cavalry would be a huge advantage for them. According to Portuguese merchant Duarte Lopes who traveled to Angola in 1578, “One cavalry soldier is equal to a hundred blacks, who are greatly afraid of horsemen.” But despite their efforts, the Portuguese were never able to maintain a cavalry force larger than a dozen or so, and cavalry was not a significant factor in their wars against African kingdoms.

The lack of cavalry had a huge effect on all elements of warfare. Contemporary European tactics revolved around cavalry either directly or indirectly. Massed infantry formations and the pike and shot system, which was used in 16th century European armies, developed to counter the heavy cavalry. The threat of cavalry slowed down the infantry and limited its mobility as they had to stay in close formation. Early primitive firearms became popular despite their slow rate of fire because they could pierce the armor of knights, unlike the bows. Their inaccuracy was not a problem either when shooting at mass formations of plodding enemy infantry. Cavalry was used to hunt down the fleeing enemy soldiers, making victories more decisive and battles riskier. Because battles very risky, European states preferred to rely on sieges and constructed sophisticated fortresses. This led to rise of importance of artillery and melee fighting in close quarters. Cavalry was used for skirmishing, scouting and raiding, vital for the marching advancing armies. Cavalry was basically connected to every aspect of European warfare.

If you take cavalry out of the picture, the whole nature of warfare completely changes. In Angola, scouting and skirmishing was carried out by specialized local African infantry troops known as pombo who were lightly armed soldiers noted for their ability to run quickly. These were also used to pursue the defeated enemies once battles were over, trying to kill and capture as many as possible. Without the threat of cavalry charges, local African troops were able to fight in open order. In Europe, this would have been suicidal, as a cavalry regiment would quickly mop up an infantry fighting this way. But in Angola, such tactics were efficient. This limited the effectiveness of Portuguese firearms, as trying to pick off individual units advancing in open order with slow and inaccurate firearms was much more difficult than firing at a massed enemy formation slowly plodding towards you. However muskets were still useful and were slowly adopted by the African kingdoms as well in 17th century as they became more accurate and reliable. But European firearms were nowhere near being a game changer as early in history. With no cavalry to cut down fleeing troops, retreating in good order was not necessary either. African armies preferred to flee from battle individually and then rally somewhere else days later. Most of them could escape so securing decisive victories that would decimate enemy armies was harder. The lack of pack animals and cavalry for raiding was devastating for the logistics of a moving army. This meant that the armies moved slower and local population usually had plenty of time to run away, carrying food with them. As a result, sieges were hard to sustain and Africans did not build strong permanent fortresses as a result. This, combined with Africans fighting in open order, made artillery largely useless and barely worth the cost and effort to get it to the battlefield.

All of this also meant that heavy armor was not as big of an advantage for the Portuguese and could even present a significant risk in battles. The Portuguese heavy infantrymen were always too few in numbers to hold the battlefield on their own, and if their African allies fled, they could be surrounded and overwhelmed, as they would not be able to flee due to their armor slowing them down. Warfare in Angola therefore revolved around large numbers of light infantry skirmish troops armed with spears, battle axes and missile weapons. The Portuguese with their small numbers would have no chance of success on their own without employing a large number of African mercenaries and allies. However there was still a place for heavy infantry and musketeers on the battlefield, and the African kingdoms also employed such units. The Kingdom of Kongo had an elite “heavy infantry” unit of 1,000 men armed with shields which the portuguese called adargueiros (shield-bearers) and considered them the best troops in Kongo. The African kingdoms also began adopting muskets. The Portuguese units therefore served an important role as elite heavy infantry and musketeers in combination with their local African contingents, developing a sort of mix of European and African tactics, and this was the way in which warfare developed in the region. For example during the campaign against Ndongo in 1585, the Portuegese force numbered around 300 while the local soldiers recruited to assist them numbered around 9,000 and “fought in their own style.” In future campaigns, there would be similar ratio between Portuguese soldiers and their African auxiliaries.

Meanwhile the African kingdoms also learned from the Europeans and adapted to the situation. There were already extensive contacts with the Portuguese before they settled in the area. The rulers of the Kingdom of Kongo converted to Catholicism already in late 15th century after first contacts with Portuguese missionaries and sent envoys to Portugal where they learned the language. This helped them to develop diplomatic skills to deal with the Europeans, as they began to understand their culture better. A great example of use of diplomacy was Queen Njinga of Ngongo who learned Portuguese from an early age and spent much of her life fighting the Portuguese in 17th century, but also converted to Catholicism and was able to get favorable peace deals, as well as profiting from selling slaves to the Portuguese. Both of these two African kingdoms participated in the lucrative slave trade together with the Europeans. Slavery had already existed in this part of Africa before contacts with Europeans, but after the Portuguese arrived the demands increased greatly as they regularly shipped a large number slaves to the island of São Tomé and later to Brazil and north America. These slaves were mostly captives in wars that were frequently fought in this region. Those were not only wars with the Portuguese but various internal conflicts that often plagued the African kingdoms, their wars of expansion against other Africans and defense against various marauding warrior tribes. The most famous of those were the feared Imbangala whom the Portuguese began employing as mercenaries due to their fierce reputation, and also bought a lot of slaves from them. Another major European player also appeared in Angola in 17th century, the Dutch. The latter affected the power balance as kingdoms of Kongo and Matanga allied with them against the Portuguese at one point, allowing the Dutch to temporarily occupy Portuguese towns and forts, but they were eventually driven out.

How did the military organization of African kingdoms looked like? To research this topic, I read the article The Art of War in Angola, 1585-1680 by John K. Thornton, which has helped me a lot. He writes that the local Angolan armies were professional in the sense that a relatively small group of people possessed special skills and training and served as soldiers for the rest. In the Kingdom of Ndongo these special soldiers were typically called quimbares (kimbare, plural imbare) and were recruited from among either the free population or slaves who were specially trained for war. Other people were sometimes levied as support troops as it happened in Kongo in 1665. This was observed by the Capuchin priest Giovanni Antonio Cavazzi who spent long time in central Africa in mid-17th century and described how such levy looked like. Every able-bodied man had to answer the call but in the end not all were required to serve and some were sent home. The weapons they used were mostly melee close range weapons like spears, clubs and battle axes. They did have missile troops but Jesuit missionaries noted that missile exchanges only took place at the beginning of an engagement, which was then followed by hand-to-hand fighting. The Jesuits also described that the Africans trained in a special martial art called sanguar which consisted of trying to dodge and avoid arrows or the blows of opponents, “to leap from one side to another with a thousand twists and such agility that they can dodge arrows and spears.” Europeans were impressed by the such skills when they saw them displayed by the Kongolese warriors. The Dutch witnessed this as a Kongolese delegation traveled to Brazil and to the Low Countries in 1642 during the time in which they were allies against the Portuguese. The Kongolese used such skills as a substitute for defensive weapons, as shields were used only by nobility.

The estimates of size of the armies varies. The Portuguese bring us very different figures, which are often highly exaggerated. The armies in Angola probably rarely exceeded 20,000 people and moved in the range of 10,000 for big campaigns. The way in which the African armies fought also made them appear larger, as they fought in open order, with soldiers spread out fairly widely to make room for individual fighters to use their skills most effectively while still being mutually supportive. While the African style of fighting often appeared disorderly to Europeans who were used to fighting in tighter formations, there was a command structure and organization. The African armies were divided into various units which had their own flags. They also used drums and trumpets to deliver signals. The leaders of units were called quilambas (kilamba, plural ilamba) who distinguished themselves with valor. Portuguese description suggests that tactical units of the Imbangala were composed of something on the order of 125 men each, with a higher level organization of groups of 500. In big battles, these units were then combined into larger ones called mozengos. Typically, armies had three mozengos, one in the center and two on the wings. Queen Njinga had four, with the fourth one serving as a reserve in the rear. In similar fashion, Kongo armies kept their best units as a reserve as well. The tactics usually revolved around trying to outflank the opponent and keeping a strong rearguard was important. There were also specialized skirmishing units of fast light infantry which I mentioned earlier. The logistics were difficult on campaigns due to lack of food and armies used a large baggage train, called kikumba, which carried provisions. The kikumba included noncombatants who helped to prepare food.

As you can see from this overview of military tactics, warfare in 16th and 17th century Angola was very different from the popular perception of conflicts between European empires and Africans based on how such wars looked like in 19th century.

The Portuguese faced determined and organized foes and, few in numbers, did not possess any technology or tactic that would give them a decisive edge. They had to adapt and basically transformed themselves into another African army, engaging in local diplomacy and building alliances.

As this part of history is totally unknown to most people, I decided to also write a quick overview of political history of this period.

How the Portuguese established their colony in Angola and got into conflict with neighboring African kingdoms

The story begins in 1479 when the Treaty of Alcáçovas was signed, putting an end to the war between Castile and Portugal which had started as the War of the Castilian Succession in 1475. During this war, the Castilians won on land, but Portugal won on the sea, beating the Castilian navy at the Battle of Guinea in western Africa in 1478. Already in this time you had two European powers fighting for control of Africa, with lasting consequences for the future of this continent. Their victory ensured the Portuguse monopoly on trade and exploration along Africa's west coast, while Castile kept the Canary Islands. This was confirmed by the said Treaty of Alcáçovas, which gave the Portugal sovereignty over “lands discovered and to be discovered, found and to be found” in Africa.

The Portuguese soon took full advantage of this and under King João II, who began his reign in 1481, they moved quickly to expand their trade and power in Africa. Experienced mariner Diogo Cão was sent to explore the African coast further to the south in 1482. He discovered the mouth of the Congo River and continued south to explore the coast of modern-day Angola. At the time, this land was populated by a number of separate peoples, some organized as kingdoms or tribal federations.

The strongest of these was the Kingdom of Kongo. Its territory stretched over present day northern Angola, western part of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, south Gabon and the Republic of the Congo. The ruler had the title of Manikongo and exerted control over key core provinces while also maintaining various neighboring entities under his sphere of influence. Oral traditions, which we were recorded by the Portuguese in late 16th century, maintain that this African state developed out of several smaller kingdoms, namely that “in ancient times had separate kings, but now all are subjects and tributaries of the king of Congo.” At the time when the Portuguese discovered this kingdom in 1483, it was already very centralized around the town of Mbanza Kongo which the Portugese named as “the city of Congo” and compared it to the size of the Portuguese town of Évora, which was a quite important and thriving city in Portugal at the time. The rulers of Kongo were able to centralize their kingdom around the Mbanza Kongo and its large population, and transformed it into an important trade center. The people spoke the Kikongo language.

The Portuguese were initially able to establish a good relationship with the Kingdom of Kongo which was at the time ruled by the Manikongo Nzinga-a-Nkuwu. The said Manikongo showed interest in Christianity and eventually converted to Catholicism in 1491. After his baptism he took the name of João in honor of the Portuguese king. He also sent his emissaries to Portugal where they remained for nearly four years, studying Christianity and learning reading and writing, and became fluent in the Portuguese language. While he later abandoned Catholic beliefs, his son Afonso I, who became king in 1509, continued to remain loyal to Catholicism and according to his own account, sent to Portugal in 1506, he was able to win a crucial battle thanks to the the intervention of a heavenly vision of Saint James and Virgin Mary. This inspired him to establish Catholicism as the state religion of the Kingdom of Kongo. King Afonso I also adopted a coat of arms in the style of European rulers.

During this time the slave trade intensified and the Kingdom of Kongo became a major source of slaves for the Portuguese who established a sugar-growing colony on the island of São Tomé. These slaves were sold to the Portuguese merchants in Kongo and were shipped to São Tomé. They were probably captives of from Kongo's various campaigns of expansion. Contemporary Portuguese officials estimated that between 4,000 and 5,000 slaves were bought from the Kingdom of Kongo per year. But after Afonso’s death in 1542 or 1543, a violent succession struggle followed, something that would happen often in Kongo’s history.

Things would only stabilize again after Álvaro I became the Manikongo (the king of Kongo) in 1568. But as soon as he claimed the throne for himself, he was faced with an external threat. Kongo was attacked by marauding warrior tribes which were collectively called the Jagas. These were very fierce and were said to have come from the far interior. They caused considerable damage and pillaged the land. To deal with this problem, Álvaro asked the Portuguese for assistance. The Portuguese helped him by sending an expedition of 600 soldiers, mostly from the colony of São Tomé. The Portuguese hoped that Álvaro would become their vassal but this did not happen. However he did allow the Portuguese to establish a settlement. In 1575, Luanda was founded which was the beginning of permanent Portuguese presence in what would become known as Angola, situated south of the Kingdom of Kongo. Paulo Dias de Novais was appointed as the first Captain-Governor of Portuguese Angola. He was instructed by the King of Portugal to expand the Portuguese dominion in Angola by bringing in more settlers and building forts.

The Portuguese in Angola wanted to expand in interior, but this proved to be difficult as they neighbored another powerful African kingdom to the east, the Kingdom of Ndongo. The Kingdom of Ngongo was located on the territory of modern-day Angola between the Lucala and Kwanza Rivers. Its origins are obscure, mostly known from oral traditions collected by the Jesuit Baltasar Barreira in late 16th century. It seems that they were originally some sort of vassals to the Kingdom of Kongo, but eventually managed to become independent. As a result, the Kingdom of Ndongo was hostile to Kongo. They approached the Portuguese themselves already in 1518, requesting Catholic missionaries, but Portugal never sent them, likely under pressure from the Kingdom of Kongo. The Kingdom of Ndongo gave Angola its name, as the title of the ruler of this kingdom was Ngola, from which the Portuguese derived the name Angola. It was clear that the Portuguese wanted to conquer the territory of the Kingdom of Ndongo, as Dias de Novais was specifically instructed by King of Portugal Sebastian I that it would be “in the service of Our Lord and to me, to order to subjugate and to conquer the Kingdom of Angola.”

As a result open war broke out between the Portuguese Angola and the Kingdom of Ndongo in 1579. The Portuguese managed to penetrate into the interior and set important foundations of their colony of Angola, building the fort of Massangano in 1583. The Portuguese were also able to ally with some of the Ndongo nobles, called sobas, who governed their territories independently and had only paid tribute to the Ngola. Many of these switched to Portuguese side. Dias de Novais soon commanded a force of around 120 Portuguese soldiers and 8,000 Africans who had allied with the Portuguese. They won a battle against a large Ndongo force in 1585 and progressed further. Emboldened by a string of victories, Dias de Novais led an even larger force of 128 Portuguese soldiers and around 15,000 African allies deeper into interior in 1590. But the Kingdom of Ndongo had meanwhile allied with the Kingdom of Matamba and their combined army enveloped and encircled the Portuguese and defeated them. Due to a disciplined rearguard action, part of the Portuguese force, including Dias de Novais, was able to escape. However this and other setbacks meant that the Portuguese were not able to fully conquer Ndongo. A peace was eventually made in 1599, where a border between Portuguese Angola and the Kingdom of Ndongo was also agreed.

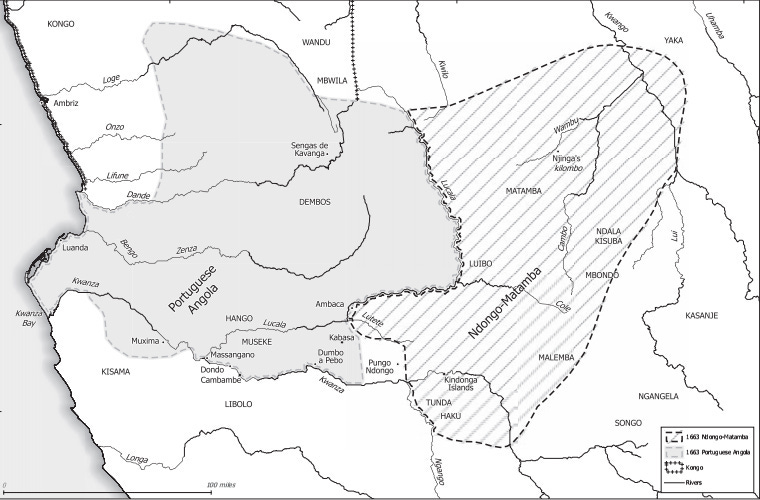

The territories of Portuguese Angola and the Kingdom of Ndongo.

But despite this peace treaty, conflicts between Portugal and Ndongo continued in the 17th century. The Portuguese advance put the Kingdom of Ndongo under continuous pressure because the Portuguese, as a powerful faction in the region with significant resources, could disrupt their internal politics by supporting various dissident factions and claimants to the throne. The Portuguese also began using fierce African warrior tribes as mercenaries, most famously the Imbangala, who had a ruthless reputation. The Imbangala were fierce warriors and marauders who kept ravaging the Kingdom of Ndongo and sold their captives as slaves to the Portuguese. The Portuguese did not like certain Imbangala customs, and often saw them as not disciplined enough, but they were valuable as partners and auxiliaries, as they kept providing the Portuguese with valuable slaves and ravaged the lands of their common enemies.

The Portuguese colony of Angola grew considerably over these decades. Luanda was granted the status of a city in 1605 and more settlements and forts were built. By 1617 another Portuguese settlement Benguela developed into a town, becoming another important trade center in the region. Angola was particularly valuable for the Portuguese as a colony due to trade links with the New World, which included exporting a large number of slaves there, mainly to Brazil.

But relationships with neighboring African kingdoms deteriorated further. This was largely due to Portuguese alliance with the Imbangala who kept pillaging everything left and right. A war would also break out between Portugal and Kingdom of Kongo. The tensions between these two former allies went back to the 1590s when, during the campaign against the Kingdom of Ngongo, the Portuguese devastated some of the lands that Kongo regarded as under its sovereignty. A further problem occurred when the Imbangala mercenaries employed by the Portuguese also pillaged the lands of Kongo. A war would eventually break out in 1622, the first in the series of several Kongo-Portuguese wars over the same century. That year the Portuguese invaded the forest land of Kazanze, a Kongo vassal, as many runaway slaves from Portuguese Angola were hiding there. The Battle of Mbumbi between the Portuguese forces and Kingdom of Kongo would follow that same year, with the Portuguese victorious. The bulk of the Portuguese army were the Mbundu archers supported by Imbangala mercenaries and Portuguese heavy infantry. This battle permanently destroy Kongo-Portuguese friendship and resulted in anti-Portuguese riots in Kongo. The newly crowned King of Kongo Pedro II had to protect the fleeing Portuguese merchants from the wrath of the population. The Portuguese merchants in Kongo and Angola did not support the war as trade suffered, and showed loyalty to the King of Kongo while being angry at the Portuguese governor.

Pedro II soon raised his full army and was able to defeat the Portuguese in a battle near Mbanda Kasi the next year. He tried to protect the Portuguese merchants on his territory but kept putting pressure on Portuguese Angola. Being knowledgeable in European diplomacy, he sent a letter to the Portuguese enemies the Dutch proposing a joint attack on Angola with a Kongo land army and a Dutch fleet, offering generous rewards to the Dutch for this alliance. The Dutch, who were enemies of the Portuguese and wanted Angola for themselves, were eager to accept this offer. The famed Dutch admiral Piet Heyn arrived in 1624 to carry out the attack. However while the attack was being planned, Pedro II died and his son Garcia I succeeded him as the King of Kongo. The latter was not fond of the alliance with the Dutch, as he felt that they should not ally with non-Catholics to attack fellow Catholics. But Garcia did not last last as he was ousted two years later in 1626. Meanwhile the Dutch were determined to attack Luanda and eventually invaded Angola on their own in 1641. The Dutch renewed the alliance with Kongo with the new king Garcia II. The joint Kongo-Dutch forces achieved further victories against the Portuguese.

At the same time the Kingdom of Ndongo and Matanga, led by the warrior queen Njinga (sometimes also called Nzinga), also entered the anti-Portuguese alliance with the Dutch. Queen Njinga became a very prominent figure during this time. Her father Kilombo was the ruler of Ndongo and she learned to read and write in Portuguese when she was very young. This skill would greatly help her in diplomacy, as she helped to make peace between the Portuguese and Ndongo in 1621. She was also baptized as Christian on this occasion, adopting the name Dona Anna de Sousa. But she was soon involved in various power struggles in her native land, eventually assuming rule over Ndongo in 1624 and fought wars against the Portuguese and their allies, but two years later she went into exile to neighboring Kingdom of Matamba, where she became queen in 1631. By 1640s she gained a lot of power through various alliances and earned a lot of money by selling slaves to the Dutch. She attacked the Portuguese with a strong army and defeated them at the Battle of Ngolomene at Kweta in 1644. But in 1646, the Portuguese raised a strong army consisting of 400 Portuguese soldiers and military officers, and possibly as much as 30,000 African allies. This army also had 16 cavalrymen and artillery. They were able to defeat Njinga's army at the Battle of Kavanga but failed to capture the queen who escaped. This would come back to haunt them as Njinga returned to fight very soon. Together with her allies the Dutch, she was able to defeat the Portuguese and their African allies at the Battle of Kombi in 1647. The warrior queen would keep fighting the Portuguese until a peace treaty was signed in 1656, as both sides became financially exhausted by the war and wanted to continue with the lucrative slave trade. Following the peace treaty, Njinga focused on rebuilding her kingdom and tried to make contacts with Christian rulers in Europe, seeking international recognition for her Catholic kingdom.

The warrior queen Njinga leading her army into battle. A contemporary European depiction.

Meanwhile the Portuguese reclaimed Luanda from the Dutch in 1648. The relationship with the neighboring Kingdom of Kongo continued to be bad and eventually another war broke out in 1665, resulting in the Battle of Mbwila. There the Portuguese led by a capable local commander Luís Lopes de Sequeira defeated the forces of King of Kongo António I who was trying to make an anti-Portuguese alliance with Spain, similar to the one Kongo made with the Dutch decades prior. António died on the battlefield, leaving Kongo in yet another sucession crisis which eventually led to a series of civil wars from which the kingdom, while remaining independent until 19th century, would never recover. The Portuguese tried to intervene in the civil war in Kongo in 1670 by attacking the neighboring state of Soyo, which gained independence during the chaos, but suffered a devastating defeat.

The Kingdom of Matamba, which had incorporated what was left of the Kingdom of Ndongo, basically becoming its successor, was in similar chaos following the death of queen Njinga in 1663. Several rulers changed in the following years. In 1680 the throne was assumed by Njinga's nephew Francisco Guterres. In 1681 he made some aggressive moves which angered the Portuguese after he invaded the neighboring Imbangala territory of Kassanje and raided Afro-Portuguese slave traders. The Portuguese sent the victor of Mbwila, Luís Lopes de Sequeira, to destroy Guterres' forces. The Battle of Katole would follow, with the Portuguese hoping they would able to defeat the forces of Matamba to such extent that they could end the independent existence of this kingdom. But the battle was very bloody for both sides, and both Francisco Guterres and Luís Lopes de Sequeira died. The Portuguese kept the battlefield, but had suffered too high losses to pursue any further goals.

The Kingdom of Matamba remained independent despite several more Portuguese attempts to conquer it. Francisco Guterres was succeeded by his sister Verónica I who had a long rule until 1721. She styled herself as the Queen of Ndongo and Matamba and kept attacking the Portuguese territories in several unsuccessful attempts, hoping to regain the borders of the Kingdom of Ndongo from early 17th century. The Portuguese launched a large scale invasion in 1744, but the forces of Matamba were able to defeat them. At the time, the ruler of Matamba was Verónica's granddaughter Ana II. She signed a treaty of vassalage with Portugal, but kept the de facto independence of Matamba, which would continue to be independent until mid-19th century.

This was just a brief overview of this extremely interesting part of history, and I hope you enjoyed it as much as I did researching it during the last few days.

This is by far one of the most respectful, transparent and reliable essays on colonial warfare pertaining to this period of African history that I’ve ever read.

As someone who descends from Italians and Portuguese families I cannot express the satisfaction and appreciation I feel at such a competent representation of this historical period and all national, sub national, supra national and international agents and events involved.

The reference to envoys needs to be emphasized as it makes it clear that in the early days of their contacts with Europeans the African kingdoms were powerful enough to be recognized as having international standing equal to that of the European kingdoms. This history had to be suppressed and concealed beneath the mythological and “unknown Dark Continent” that justified colonialism in Africa.