The Rise of the Habsburgs: The Battle of Guinegate in 1479

The marriage that changed European history and the beginning of French-Habsburg rivalry.

The rise of the Habsburgs is one of the most remarkable stories in European history. During the middle ages, this old dynasty used to be a minor player in European politics based in an obscure borderland of the Holy Roman Empire that gave it the name House of Austria. Yet as Europe was entering a new age at the end of the 15th century, the Habsburgs quickly began their rise to become the most powerful dynasty in Europe in a matter of decades due to successful dynastic marriages. From 1477 to 1526, they inherited one by one the territories of Burgundy, Spain (Castile and Aragon), Bohemia and Hungary. The Habsburg ruler Charles V, who became Holy Roman Emperor in 1519, would end up ruling over vast domains in Europe as well as territories in the New World, becoming the most powerful European ruler since ancient Rome. His motto “plus ultra” (further still) embodied the Habsburg ambition for universal monarchy.

In a series of articles I will examine this rise and explore some of the overlooked details that were important, especially when it comes to military history.

The unexpected rise of the Habsburgs is commonly proverbially explained with the famous phrase “Bella gerant alii, tu felix Austria, nube” (let others wage war, but you, happy Austria, marry).

But this phrase is only half-correct. While the dynastic marriages were crucial for the Habsburg rise, they also had to wage war. A lot of wars, in fact. The golden era of Habsburg power was also the period of European history marked by brutal wars and the Habsburgs were involved in almost all of them. Practically everything they gained through marriage had to be viciously defended on the battlefield at some point. Conflicts like the Italian Wars (1494-1559), the Eighty Years’ War (1568-1648) and the Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648) would define the Habsburgs along with their long and grueling conflict with the Ottomans. It’s impossible to understand the rise of Habsburgs without understanding the nature of these wars.

Yet before the crucial dynastic marriages, before the expansion, before the wars, there was a dream. It all started with a crazy ambition of a man who had no business of dreaming so big.

There was a dream that was Rome. You could only whisper it. Anything more than a whisper and it would vanish, it was so fragile.

From movie Gladiator (2000)

In 1437 Frederick III of Habsburg, the great-grandfather of future mighty Emperor Charles V, wrote down a mysterious acronym A.E.I.O.U. This acronym would become his slogan and became associated with the Habsburgs ever since. But no one really knew what the meaning of it was. It was later discovered in his notes that it was supposed to stand for “Austriae est imperare orbi universo” (all the world is subject to Austria). Austria referring to the Habsburg dynasty, the House of Austria. Although this acronym will always be shrouded in mystery, it was later interpreted as an ancient prophecy that the House of Austria was destined to establish a universal empire.

At the time Frederick III was merely the Duke of Styria, Carinthia and Carniola, the Habsburg lands of Inner Austria, which would make his prophecy that much more bold. But he was an ambitious man and it wouldn’t be that surprising if he secretly played with the idea of great glory awaiting him and his dynasty. It seems that the A.E.I.O.U. slogan was indeed a whisper of a big dream that no one really dared to say out loud.

Whatever the true meaning of the acronym was, the imperial dream was definitely present among the Habsburgs long before they established themselves as the most powerful dynasty in Europe. The ambition was always there. Even before the days of glory and might they carried themselves with special dignity.

Frederick III embodied this. In 1452 he was crowned Holy Roman Emperor in Rome, the first Habsburg to hold the title of Emperor. Even though he did not hold much actual power as a mere provincial duke and was so poor that the Pope had to pay expenses for his trip to Rome and coronation, he nevertheless had big ambitions that matched the splendor and prestige of his title.

But Frederick’s reign was plagued with all kinds of difficulties. The Habsburg possessions were small to begin with, and even those were divided among his relatives with which he quarreled. He fought against his brother Albert VI for control of Archduchy of Austria and ultimately outlived him, becoming the sole Archduke in 1463.

Even in Central Europe, the Habsburg position was weak. The Archduchy of Austria neighbored the powerful Kingdom of Hungary of Matthias Corvinus who assembled the legendary mercenary Black Army, most likely the strongest army in Europe at the time. Corvinus had been a rival of Frederick for a long time and beat him to the throne of Hungary in 1458 after the early death of Frederick's Habsburg cousin King Ladislaus the Posthumous. Frederick was one of the candidates for King of Hungary but had to concede the kingdom to Corvinus, an aggressive expansionist who was determined to conquer his neighbors in Central Europe, waging wars against Bohemia and later against Frederick as well. The Habsburgs had no answer for the mighty mercenary Black Army which ultimately conquered Vienna in 1485, forcing the humiliated Frederick to flee. It would be only after Corvinus’ death in 1490 that the Habsburgs were able to push back and reclaim all of their lands that were lost back.

Because of such defeats, Frederick III’s reign is not remembered as gloriously as that of future Habsburg rulers. For all his pretense of imperial splendor and his great ambitions, he had very little to show for it. But there is a lot to learn from him. He displayed the most necessary trait needed at the time, perseverance. He had no funds nor an army, but he prevailed by simply refusing to concede defeat to any of his various enemies. And this is why his title of Holy Roman Emperor and the way he carried it was so important. He did not have the means to rule as a real emperor, but his pride stubbornly kept him going. The ambition never died. He played the long game and ultimately beat his rivals by simply outlasting them.

This patient strategy worked because at the time, the medieval states did not have standing armies. They could not afford to keep funding a professional army in times of peace. Instead, the medieval armies were raised on campaign-to-campaign basis. A kingdom might be extremely powerful under a ruler who could raise large armies, but after this ruler died, the ability to field such armies could disappear in a moment. This is what ultimately happened to Hungary. The mercenary Black Army was expensive and relied on Corvinus squeezing the nobles dry to pay for it. But after Corvinus died in 1490, there was no powerful ruler next in line to keep providing the means for this huge army. Instead, the nobles got their way and stopped paying high taxes. The money for Black Army vanished. And just like that, the strongest army in Europe evaporated. Suddenly, the balance of power in Central Europe changed completely, allowing the Habsburgs to regain what was lost.

In this way, the medieval wars were often not won by the strongest but by the most patient. And this was the trait that Frederick seemed to have had in abundance, patience.

However the most important event during Frederick’s reign happened earlier in 1477, the marriage between his only son Maximilian and Mary the Rich, the daughter of Duke of Burgundy Charles the Bold. It was a marriage Frederick planned and helped to set up and it would become one of the most important marriages in European history.

The marriage between Maximilian and Mary was first discussed by Frederick III and Charles the Bold in Trier in 1473. Both were ambitious men and both had what the other lacked. Charles the Bold ruled over what historians now name Burgundian State, a vast complex of territories along the western frontier of the Holy Roman Empire which included the prosperous Flemish cities of the Low Countries. Called the Grand Dukes of the West, the Dukes of Burgundy had significantly expanded their might during the 15th century and in 1467 Charles the Bold inherited a wealthy and powerful state, becoming one of the most imposing rulers in Europe. But for all his power, he was still merely a duke. He was the opposite of Frederick who held the prestigious title of the Emperor but didn’t have the resources to do anything. Charles wanted the Habsburg Emperor Frederick to crown him as king to elevate his prestige and his dominions. As part of the deal, Charles’ daughter Mary, his only heir, would marry Frederick’s only son Maximilian. This is what they discussed when they met in Trier.

Everything was already agreed, but Frederick being himself, he decided to pull out of the deal in the last minute. He decided to simply flee during the night. Apparently the cocky demeanor of the ambitious Duke instilled doubt into Frederick, fearing that by elevating Charles into King he could potentially become too strong of a rival to him in Imperial politics. It is precisely because of such timid calculative approach and the disgraceful manner in which he handled affairs like this, that Frederick is not looked upon as fondly as his successors. But his games always seemed to work. He “dealt” with the ambitious Duke of the West the same way he “dealt” with his other rivals like his brother Albert or decades later with Matthias Corvinus. He would end up simply outlasting him.

For Charles the Bold was very much like Matthias Corvinus whom I already described. He was able to field a large army of knights and mercenaries, professional and trained warriors that gave him the edge in wars and terrified his enemies. But the funds for this army came from squeezing the wealth of his subjects which he was able to do because of how terrified they were of him and his army. Just like Corvinus kept his nobles in check, Charles the Bold kept the rebellious wealthy Flemish cities in fear. He created a system which relied on him and in which he was the central figure. But living up to his nickname and his personal motto “Je lay emprins” (I have dared), he was also a risk taker who put everything on the line. And he would soon lose everything.

Soon after the fiasco at Trier, Charles the Bold would become involved in the Burgundian Wars, a bloody conflict which lasted from 1474 to 1477. Trying to expand his power and influence eastward, Charles the Bold faced the Duchy of Lorraine and Swiss Confederacy. It would be the incredible military valor of the latter that would lead to Charles’ downfall. The Swiss were a warrior people who had pioneered infantry tactics, fighting with pikes and other polearm weapons and relying on their discipline and fighting spirit with which they were able to simply overwhelm the enemies. They took no prisoners and never surrendered. Historically, the Habsburgs were also bitter enemies of the Swiss. Just like Charles the Bold, they found out about the Swiss valor the hard way, losing the battles of Morgarten in 1315 and Sempach in 1386 while trying to invade Swiss lands. These ancient victories were the foundation of the powerful Swiss Confederacy which would go on to also win the Burgundian Wars, defeating the mighty Burgundian army in battles of Grandson, Morat and Nancy.

In a way similar to Frederick III, Charles the Bold was a man too proud to give up and concede defeat. But in his case this led to his downfall. In the ultimate battle at Nancy, the Grand Duke of the West died fighting the hated Swiss on 5 January 1477.

This left Charles’ daughter Mary in charge of Burgundy as his only child, earning her the nickname Mary the Rich due to the rich inheritance she received from her father. But the mighty Burgundian State was crumbling. The burghers of Flemish cities who had long endured the terror of Charles the Bold finally saw an opportunity to assert themselves and demanded back the old privileges which the mighty Dukes of the West took away from them. The Burgundian military power was in ruin, with many knights and trained militias having died in the disastrous Burgundian Wars.

But the greatest threat came from the old enemy France. Following the death of his bitter rival Charles the Bold, French king Louis XI immediately seized the opportunity to attack. He invaded Burgundy and started conquering.

With the powerful Burgundian State crumbling, France seemed destined to become the unrivaled most powerful state in Europe. Decades prior to that, France had finally emerged victorious from the Hundred Years' War against England in 1453. France was the most centralized and modernized state in Europe, able to provide resources to field large armies from the vast royal domains directly owned by the French kings who became eager to pursue an aggressive expansionist policy and the path for eastward expansion seemed open.

As the Duchess of Burgundy, Mary was now the only one standing between France and its expansionist ambitions. Despite the pressure, she took an unyielding approach, determined to keep what was left of the Burgundian State together in face of the French threat. She committed to marriage with Maximilian of Habsburg, the marriage already discussed years ago by their fathers. It took place at Ghent on 19 August 1477. Mary was 20 and Maximilian was 18 at the time. It proved to be a crucial historic decision since this marriage would enable the rise of the Habsburgs and give birth to the French-Habsburg rivalry that defined the next centuries of European history.

Mary was popular in Burgundy and it also helped that there was a strong cult that associated her with Virgin Mary. This was skillfully turned into political propaganda that would end up benefiting Maximilian as well. During the crucial year of 1477, the poet Jean Molinet wrote Le naufrage de la Pucelle (Shipwreck of the Virgin), the Virgin in this story being an allegory of both the Virgin Mary and Mary of Burgundy. In this work, after the death of her father, the Virgin was left in charge of the ship, which was attacked by whales and other sea monsters. The sea monsters represented France which wanted to take hold of Burgundian territories. Eventually an eagle appears as a savior, symbolizing Maximilian and the Holy Roman Empire. The story is full of religious mysticism, symbolizing the marriage of Mary and Maximilian as a mystical holy union of the Virgin and the Eagle. It was a powerful way to represent Maximilian as a savior of Burgundy.

This sort of mysticism and symbolism always accompanied the Habsburg rise to power. The Habsburgs understood the power of such legends and myths. This brings us back to the mysterious acronym A.E.I.O.U. used by Frederick III. He spent his entire life trying to pave way for Habsburg rise to hegemony over Europe, and his son Maximilian now had the opportunity to carry the torch as the new Duke of Burgundy, ruling over wealthy lands that would finally give his dynasty the ability to expand.

But Maximilian was very different from his father Frederick and the two never got along. Maximilian’s mother Eleanor of Portugal also disliked Frederick. She was raised in the lavish court in Portugal and was homesick having to live in Austria with her stingy husband. But most of all she disliked Frederick’s timid, nonbelligerent and calculating approach. She wanted her son Maximilian to be completely different from his hesitant father, and raised him to be more warlike. “If I had known, my son, that you would become like your father, I would have regretted having born you for the throne,” she once remarked. And indeed, her wishes came true as Maximilian would become the total opposite of his father. Maximilian enjoyed fighting, tournaments and taking risks. In many ways he was a throwback to the old days of chivalry, earning himself the nickname “the last knight”.

However there is one thing that Maximilian shared with his father, ambition. They had a very different approach to rule but both wanted the same thing, to achieve the dream of the Empire. And it seemed that both of their approaches were right in the specific circumstances they ruled under. Frederick persevered in the dark days, Maximilian was ready to go to war as a ray of light started to finally shine on the Habsburg dynasty and revealed a historic opportunity. The marriage of Maximilian and Mary of Burgundy suddenly put Habsburgs on the map as one of the most powerful dynasties in Europe, but what was gained through marriage had to be paid on the battlefield with blood. The young Maximilian understood that and was ready to face the full onslaught of France.

“There stood the count of Romont right in the formation, and over there stood the Duke among the common soldiers on foot and among the pikes.”

Chronicle of the battle of Guinegate (1479)

The young Duke Maximilian had to rule his newly acquired lands as a true impresario of war. He was still young and inexperienced, but he displayed the most important trait one needs to have to build an empire, audacity. Everyone expected that the war against France would be fought defensively. No doubt Maximilian’s father Frederick would have also tried to take this approach, trying to exhaust and outlast his enemy like always. But Maximilian saw things differently. He decided to go on offensive and bring the war to the enemy, meeting the French on the open battlefield!

Just like there is a lot to learn from Frederick’s patient approach, there is a lot to learn from Maximilian. If you want to build a powerful empire, at some point you will have to take risks, and it’s better to take these risks sooner than later. This way you can rally the people who are willing to go on this crazy journey and filter out the timid ones as soon as possible. By taking an aggressive approach to war, Maximilian took over what was left of the Burgundian military power and rallied the most willing and the most dedicated ones to the cause, the ones who were willing to share his dream and his audacity.

One of these men proved to be crucial for the upcoming war. He was Jacques of Savoy, the Count of Romont. He was a close friend of Charles the Bold and served him loyally as one of the commanders in the Burgundian Wars. Fighting against the Swiss, Romont had already experienced the darkness of defeat. He saw painful images of his heavily defeat army returning from a failed campaign. Yet the best warriors and commanders were always those who could bounce back from defeats and learn from them. Romont learned a lot from the Swiss. He was always close to them as his possessions were situated in the neighboring area of Bern and Fribourg, on Neuenburg Lake. In the Burgundian Wars, he learned of the superiority of the Swiss military tactics and wanted to implement them in his own army, now serving the new Habsburg Duke of Burgundy. Maximilian was open to such ideas. Here is another trait we can observe in the rise to power of successful empires, the willingness to learn from your enemy and copy his style of fighting if needed. Maximilian himself started drilling with the long pikes in the Swiss manner. He had them produced in his new domains in the Low Countries and his troops were starting to learn the Swiss way of infantry fighting.

This would turn out to be crucial in the open battle against the French that would follow at Guinegate in 1479. The forces of Habsburg Burgundy would have to face the powerful French army famous for its heavy cavalry of trained knights. The Burgundian heavy cavalry was depleted as many knights died in the Burgundian Wars. Therefore the key to victory would be through infantry. It was a very dangerous strategy but it helped that the Burgundian noblemen like Romont also knew the French way of fighting very well. The French were organized in a very similar manner to the Burgundian army of Charles the Bold. They were divided into compagnies d'ordonnance and their infantry consisted of franc-archers, a multi-use unit armed with bows and swords. While such army looked good on paper, the Burgundian commanders realized the vulnerability of this system through their own experiences against the Swiss. The franc-archers were trained in the use of both ranged and melee weapons. They also rode horses as mounted archers but dismounted in pitched battles. The problem with such troops was that they were not elite in any type of fighting. A spirited infantry in the manner of the Swiss that was focused solely on melees with pikes and other pole weapons would rout them in melee, and as the Burgundian Wars showed, a specialist elite infantry would fare better in battles overall.

The key to beating the French, however, was in defending from the dreaded cavalry charge. But here the Swiss way of fighting provided the answer as well. In fact, it was originally intended as anti-cavalry system. The Swiss fought in large squares and used long pikes to defend themselves from cavalry. Furthermore they trained to maneuver with pikes to be able to quickly turn in different directions and prevent being flanked. Romont trained Burgundian Flemish infantry in such manner. The Flemish had already used their own version of infantry tactics successfully against French knights in history such as in the battle of Courtrai in 1302 where they also used terrain and obstacles to stop the cavalry charge, but the advanced Swiss tactics were new to them as well. Trying this approach against the mighty French knights was always going to be a gamble. But it was a gamble that Maximilian was willing to take.

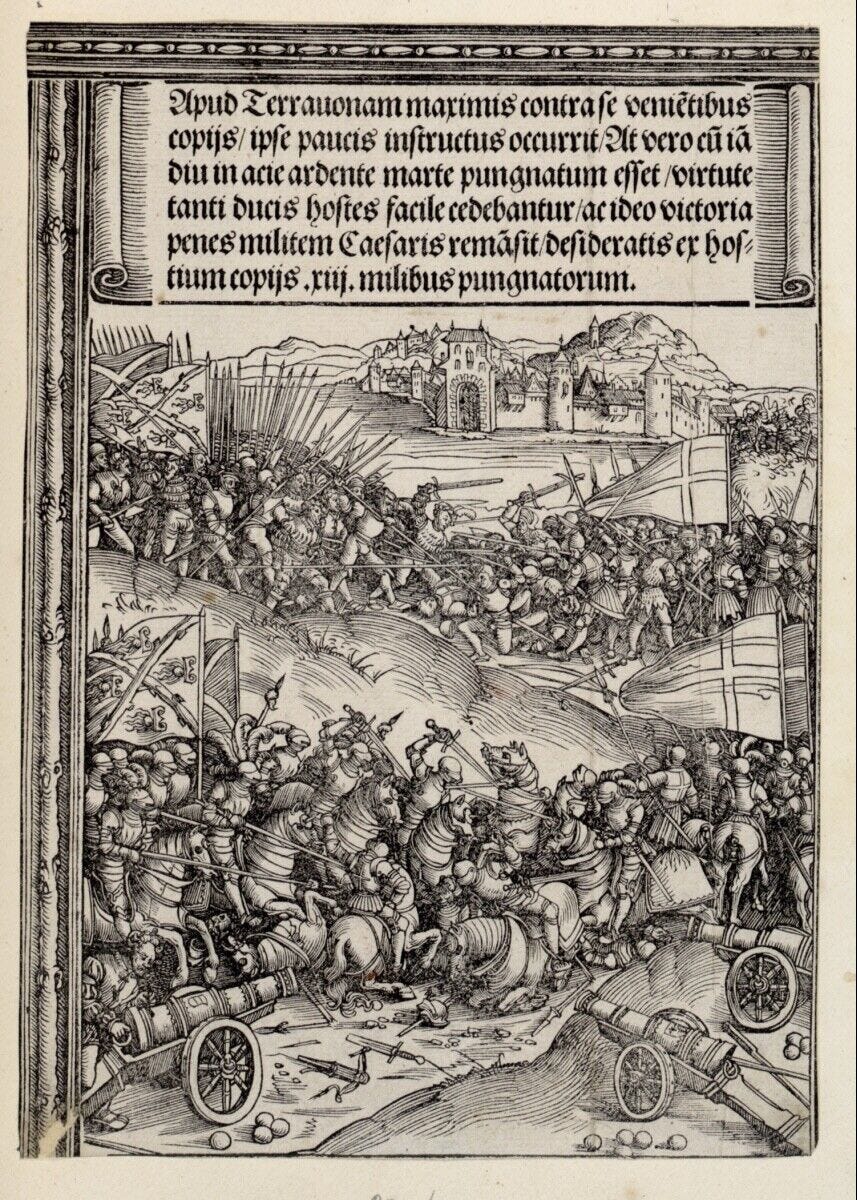

The battle of Guinegate happened following Maximilian’s counter-offensive in the Burgundian Low Countries as he tried to capture the border stronghold of Thérouanne to push back the French. The French sent a relief army and an open battle would follow on 7 August 1479. Both armies had around 16,000-20,000 men, depending on different estimates. The French had an advantage in cavalry but the Burgundian infantry was better and had more variety. On top of the pikemen recently trained in Swiss style of war, the Burgundians also hired English and German mercenaries who provided archers, crossbowmen and arquebusiers. Both sides also used artillery and it seems that the Burgundians also used war wagons likely brought by their Central European mercenaries.

Both armies placed infantry in the center and put cavalry on both flanks. However the Burgundians positioned their infantry in Swiss style, within two large squares. One was commanded by Romont and the other by Engelbert II of Nassau, another brave Burgundian nobleman who was loyal to his new ruler Maximilian. Meanwhile the French were commanded by Philippe de Crèvecœur d'Esquerdes, Maréchal des Cordes. He was one of Burgundian nobles who switched to the French side following the death of Charles the Bold. He now served the French king Louis XI who wasn’t present at the battle.

Such open battles were a rare event in the middle ages due to the risk they presented for both sides. Yet when they happened they were always a majestic sight. The two large armies stood face to face, flying their ancient banners. The French fleur-de-lis on one side, the Burgudian cross and Imperial eagle on the other. Noble knights displaying their coats of arms, city militias proudly carrying their standards. The intimidating weapons and war horses. Everything was on the line. But Maximilian wanted this. He decided to take even more risks. He dismounted to fight as a common infantryman among the pikemen! He was joined by a number of noblemen who also dismounted to strengthen the pike square and to provide the necessary fighting spirit among infantry.

And this is one of those special moments in history that made me love the Habsburgs. The way that Maximilian and the Habsburg dynasty challenged the course of history and made it all about themselves. Because without their bold actions, the French would have become the dominant power in Europe in the 16th century. They should have. They were the powerful centralized power from the prosperous part of Europe. But at Guinegate, a member of a poor dynasty from an obscure backwater borderland decided to challenge them and blocked their path to expansion. Maximilian stood in front of the best the French could throw at him, in the front line among common pikemen, displaying the audacity to challenge the superpower. The kind of audacity that was essential to build his own empire and inspired his troops to fight for him.

Furthermore Maximilian was the only male heir of Emperor Frederick III. He put the future of his entire dynasty on the line. The Habsburg story was going to either begin or end that day.

The battle of Guinegate commenced. The French under des Cordes took the aggressive approach. He charged with knights on his right flank and routed the Burgundian mounted knights. This enabled the French to capture the Burgundian artillery and put immense pressure on the Burgundian infantry square on the left commanded by Nassau. However the Swiss pike tactics prevented a total disaster and kept the French cavalry at bay. Still, the French fire from artillery and archers was inflicting casualties. Meanwhile on the right, the Burgundian cavalry managed to hold off the French cavalry. This proved to be crucial because it gave the infantry square on the right commanded by Romont an opportunity to go on the offensive and ultimately relief Nassau’s infantry. This was also a chance for the young Maximilian to show his valor in battle and indeed the chronicles praise him, “Duke Maximilian bravely stood firm with his pikemen, so that the French cavalry, which sought to attack him from both sides with their other men, could not prevail against him.”

The battle turned into a grueling melee and ultimately the Burgundian tactics and the valor of their infantry prevailed. Romont’s infantry square helped Nassau’s and pushed back the French infantry. The French were not able to break the pike tactics and their infantry routed, forcing the knights to retreat as well.

The victory at Guinegate ensured that the Habsburgs kept their newly acquired Burgundian territories and kept the French at bay. Even though Maximilian couldn’t exploit the victory for further military gains due to lack of funds and opposition from provincial estates, the most important aspect of this victory was symbolic. Maximilian put entire Europe on notice. The triumph at Guinegate and his personal bravery put prestige to his name and to Habsburg ambitions. It was at Guinegate that the legend of Maximilian and the House of Austria started. The union of the Virgin and the Eagle chased away the monsters like the legend predicted and the imperial dream was kept alive. For the Habsburgs, symbols and legends like this were always a powerful fuel for their cause.

But there was also another important element of Guinegate. The successful implementation of Swiss tactics proved that this military system could be copied and adopted. It would lead to the rise of the Landsknechts, the German mercenaries trained in Swiss tactics who would be at the disposal of Habsburg Emperors in the future and contributed to future military success significantly. Already in the 1480s, such Landsknecth regiments would be raised.

The Habsburgs would soon need these Landsknecht mercenaries badly. For Guinegate was only the start of the Habsburg rise to power, and more bloody battles would follow. But more about this next time.

Nice post - I am wondering how Frederick III managed to become Holy Roman Emperor considering the weak position you describe here?

Fantastic! Keep up the good work!